Exhibits Origins of the NAEB and Educational Media

Affiliates of the National Association of Educational Broadcasters (NAEB) built American public media between 1925 and 1967, making it one of the central trade organizations of American media history. Its history gives us an opportunity to trace the key players, events, and content that engendered our community, public, and distance learning institutions.

Education for All

In the early-20th century, state universities initiated distance learning for rural populations, followed by the licensing of the first educational radio stations in 1921. Around this same time, the first educational broadcast genres began to emerge. Programs consisted of home economics, music appreciation, language acquisition, agriculture, and “how-to” content. Many of the genres that we associate with public media, and more recently cable television, derived from refinements of state university curricula.

Because educational radio was typically an extension service of state programs, educators felt strongly that their approach to media should reflect a public-school ethos, which meant that radio content be free, uncompromised by a profit motive, and provide skills to anyone within the confines of the state. Influenced by the philosophy of John Dewey, educational radio innovators understood their project to be a new type of “intentional agency,” one that would circulate information similarly to newspapers, but take the form of lecture and instruction.

In contrast to early commercial media industries, which were originally founded as promotional extensions of businesses and manufacturing, educational technologists sought to utilize radio to increase equal access to education. Many early letters in the 1920s and 1930s detail this aspiration, and it can be argued that the origins of public media in the United States materialized from these conversations about the primacy of equity to information.

Early Organizing Efforts

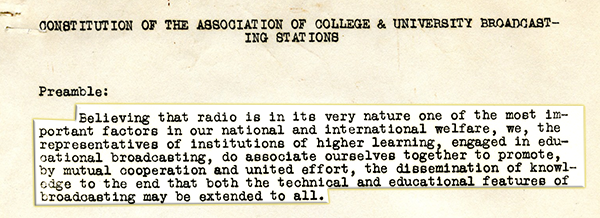

The National Association for Educational Broadcasters (NAEB) was founded in 1925 as the Association of College and University Broadcasting Stations (ACUBS). The ACUBS’s primary purpose was to facilitate communication between public universities regarding the development of distance learning programs. As a clearing house for noncommercial institutions, the ACUBS Constitution was consequently written in the tenor of speculative language around cultural goals, more than as a statement of best practices:

The principal anchors of early education radio from the 1920s-1940s were the University of Wisconsin, Ohio State University, Iowa State University, University of Iowa, University of Illinois, and to a lesser extent the Universities of Minnesota and South Dakota. Their main concern was accumulation and maintenance of memberships so that the ACUBS ledger could appropriately detail the state of the field.

The second dominant theme in early letters was over how to produce a model of radio communication, which they called “Schools of the Air,” that would differ from commercial broadcasting. Conferences were held between 1928 and 1934 to discuss a range of technical practices--from how to conduct live drama, to questions such as how to set up a studio.

This debate over whether educational programming should be instructional or informative entertainment would run until the 1980s, and represented an important fracture between educational and public media practitioners: Midwestern institutions were intent to maintain a lecture format, while East Coast proto-public stations endeavored to build a “fourth network” that could aesthetically rival commercial broadcasters.

The Communications Act of 1934

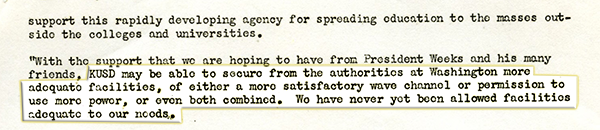

A third issue that shows up in early correspondence focused on how to maintain station licenses. Early members supported the concept that a certain percentage of all frequencies should be set aside for non-commercial purposes. In a key twist in the early development of American broadcasting, the Communications Act of 1934 – the first comprehensive media policy – changed the rules for station licensure. Few universities were able to meet the Act’s demanding technical standards. The act also codified previous policies set by the Federal Radio Council (FRC) that were unfriendly to noncommercial use of the airwaves.

In spite of support from the military, Office of Education, and philanthropic groups, educational stations were at best an incipient endeavor in the 1930s, having a poor understanding of discourses in the regulatory sector. So despite being advised to take a more active role in national debates, ACUBS was poorly equipped to take part in or influence these developments.

Before legislators settled on a national policy, the ACUBS was offered reserved experimental frequencies in the 1500 and above band but turned the offer down. Unfortunately, members did not have a backup plan, and educational broadcasters were blindsided by rules of the Communications Act of 1934 that stipulated sweeping “public interest” standards for transmitters, broadcast schedules, and listenership, which few universities could meet.

Records give different accounts, but there were approximately 200 educational stations by 1934. By 1935 the educational radio landscape had been decimated; only 38 stations remained. The ACUBS was further down to only 20 membership stations by the time the policy was passed. It was at this time that the ACUBS changed their name to the NAEB.

The consequence was that a corporate friendly media landscape was implemented with little resistance – beyond activist testimonial by the NCER –during FCC hearings in 1935.

Educational Media Rebuilds

While the Communications Act represented a huge blow to early experiments, educators rebounded and evolved. Over the next fifteen years NAEB members regrouped, built alliances, and began to lay out a plan to rebuild noncommercial media. The NAEB began to study what had made commercial broadcasting so successful. The use of the term “Public Radio Broadcasting System” was first coined in the months subsequent to the 1935 FCC hearings, by Dr. Arthur G. Crane of the NCER and University of Wyoming. Members explored early audience and policy analysis, and their methodological breakthroughs in the 1930s and 1940s influenced the emergence of political economy of communication research.

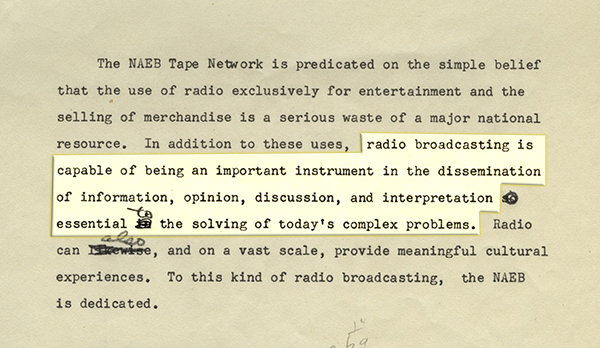

Membership numbers also dramatically increased after 1934. In 1936 the Rockefeller Foundation invited BBC consultants to visit educational stations in the U.S., and station managers took internships at NBC and CBS to study radio aesthetics. The Association began to relay quality programming to help smaller and less organized university stations keep their licenses. The NAEB experimented with shortwave retransmission but settled on the printing of records for regional distribution, which they called program transcriptions.

By World War II noncommercial media defined itself as non-profit, while focused on following Communications Act regulations while maintaining an educational vision. The NAEB settled on programming genres derived from distance and adult learning coursework, and instituted a decentralized distribution structure. After WWII the NAEB moved to the University of Illinois, and members built a program transcription library for distribution of quality noncommercial programs. In the early 1950s the auspice of a fourth network became centralized through NAEB activities, which synthesized the work of multiple universities, media research, and public policy advocacy into one institutional voice.

Josh Shepperd is an Assistant Professor at the University of Colorado Boulder and the Sound Fellow of the Library of Congress National Recording Preservation Board (NRPB). Josh is currently completing two manuscripts that interrogate the history of public media. Shadow of the New Deal: The Victory of Public Broadcasting is under contract with the University of Illinois Press. He is also slated to co-author the official update of the History of Public Broadcasting with Allison Perlman (UC-Irvine) for Current and the Corporation for Public Broadcasting (CPB). Josh sits on the Advisory Team of Unlocking the Airwaves.

![Beall, L. When I think back, Rural Electrification Administration, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Poster shows an elderly man sitting in a rocking chair and adjusting the dials on a radio. \[193-] \[Photograph] Retrieved from the [Library of Congress](https://www.loc.gov/item/2010650608/).](/static/bf992337b9c1fdfdfa7e9515f1684250/2af16/service-pnp-cph-3g10000-3g14000-3g14700-3g14733r.jpg)

Beall, L. When I think back, Rural Electrification Administration, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Poster shows an elderly man sitting in a rocking chair and adjusting the dials on a radio. [193-] [Photograph] Retrieved from the Library of Congress.

![(ca. 1922) Youthful Radio Expert. Illinois Chicago, ca. 1922. \[Photograph] Retrieved from the [Library of Congress](https://www.loc.gov/item/93510755/).](/static/290b246c30fd9fc95ea65648c6f5d749/08fc2/service-pnp-cph-3b30000-3b39000-3b39700-3b39715r.jpg)

(ca. 1922) Youthful Radio Expert. Illinois Chicago, ca. 1922. [Photograph] Retrieved from the Library of Congress.

from President Joseph Wright to ACUBS members.](/static/220471d89130a00fc5373b48182f239b/9d140/acubs-font.png)

Letterhead branding from The Association of College and University Broadcasting Stations (ACUBS), the NAEB's original moniker. From a 1933 special bulletin from President Joseph Wright to ACUBS members.